A Brief History of Fans

Learning the history of fans makes collecting them even more rewarding, explains Colin Lawton Johnson.

For an immense span of time, fans have played important roles in military, civil, religious, utilitarian and social lives of civilizations.

|

| Contemporary Spanish Fan |

Only in the past half-century have fans become valued only for their rare beauty or as interesting mementos of the past.

The English word for fan comes from the Latin "vannis" a tool to winnow grain. Prehistoric people, as well as the remote Indians of the Amazon basin today, have used hand-screens of woven grass or "fronds" to fan flames of their fires to make flour.

In Egyptian court and religious ceremonies, fans were official symbols, shown in tomb paintings and low-relief carvings, such as the one in the 12th dynasty tomb of Mereruka at Sakkarah (2366-2266BC), which depicts a royal procession with nobles carrying tall standard fans-decorated handles surmounted by feathers or other materials. Two gold-handled ostrich fans of King Tutankhamun (1352BC) were found among the treasures and household utensils which had been carefully placed in his tomb for the convenience of the young pharaoh on his journey into the underworld.

In Assyrian art (1350-612BC) many "fly whisks" are depicted: small ones with short handles of carved or otherwise decorated handles of wood, and brush, horsehair or vegetable fiber; and larger whisks of later date with feathers (shown in bas-relief panels from Nimrud, 745-727BC and from Nineveh, 681-705BC). Standard and sceptral fans, some bronze gilded, emblazoned with totemistic, symbolic or heraldic devices, were used for ceremonial purposes.

During this period, fans are frequently mentioned in the Bible. Isaiah speaks of the oxen and young asses that shall eat clean provender which has been winnowed with the shovel and fan. Jeremiah, lamenting the backsliding of Jerusalem, exclaims "I am weary with repenting; and I will fan them with a fan in the gates of the land"; and again, "Send unto Babylon fanners that shall fan her, and shall empty her land."

Punkahs, long-handled feather-fans, were used to circulate air and dissipate offensive odors in India. Members of a monastic novitiate in Burma, the shinláung, employed palm-leaf fans both as shields from the sun rays and as screens from the sight of women, moving the fan from side to side as a woman passed.

Using the fan as shield or standard, spread from Egypt to Greece and Italy. The earliest Greek fans doubtless were branches of myrtle, acacia, triple leaves of Oriental plantian and leaves of lotus. The single leaf or heart shaped fan occurs frequently on Greek terracotta and in Tanagra figure statuettes. Circular fans of peacock feathers appeared in 5th century BC, and are constantly referred to in Greek writing.

Throughout the Roman empire, "fly traps" (muscarium) were commonplace. Frequently made of peacock feathers with long handles, these could be waved by a servant, "labellifer", to protect a mistress while sleeping or an official at the table from insects. The tail of a yak, probably imported from India, was used, also small hand-sized fans of square or circular shape formed of precious wood or finely cut ivory, the latter referred to by Ovid in the third book Amores: "Wouldst thou" he exclaims, "have an agreeable zephyr to refresh thy face? This tablet agitated by my hand will give you this pleasure."

For well over two thousand years fans have been used in China. Two woven, side-mounted fans (2nd century BC) were excavated at the Ma-wang-tu tomb in Hunan province. Fans certainly existed in China long before that date as hand screens, probably feathers of pheasant or peacock, for which, at a later date, silk or silk tapestry was substituted to economize. Both sexes carried fans, and strict rules dictated which kind of fan a person used, depending on their social status. Fans were used in court and for each season of the year only a specific style fan was considered appropriate. It was not until the Sung dynasty (960-1279BC) that fan painting assumed considerable importance as an established aspect of Chinese painting; fan paintings by prominent artists were valued equally with paintings on scrolls, during religious ceremonies, and were also useful for shielding the face to avoid endless greeting rituals.

In the following centuries fan paintings were signed with both seals of the artists and the owners. The paintings were frequently removed from the fan sticks and mounted in albums. During the Chou dynasty (about 1106BC) fans were used in a more mundane way - to fan dust from wheels of chariots - presumably to keep it from being blown into the eyes of the drivers.

The earliest representation of a fan in Japan is in the 6th century burial mound on the island of Kyushu - a wall painting depicting waves, boats, horses and a human figure flanked by two upright poles topped with large oval shapes drawn with radiating lines.

|

| Ivory folding fan, "Only One Chick" Neiji Period, 1880s. The double paper leaf is painted with trees, a cottage and cranes in a misty landscape. On the reverse a cockerel, a hen and one single chick appear beneath a flowering shrub. (Courtesy of The Fan Museum Trust, Hélène Alexander Collection). |

Japan is generally credited with the invention of the folding fan, an innovation over rigid screen fans, making them smaller and easier to handle for personal use.

Various myths explain the origin: from being a gift of Cupid (a European fancy), to being inspired by a bat's wing spread against a lantern during the 7th century reign of Emperor Ten-Ji.

The probable derivation is from "mokkan" - thin, small slices of wood (about 30cm long and 4 or 5cm wide) used when writing down records. Twenty or so of these strips would be joined at one end by a thread or rivet. When flipped open the shape became a "fan". By the 10th century folding paper fans or "ogi" were widely used throughout Japan, and had been spread by way of Korea to China, perhaps by missionaries or travelers in the previous century. The earliest surviving pleated fan has paper leaves and is from 12th century Japan.

The earliest surviving Western fan is in the Bascilica of St. John the Baptist at Monza, Italy. This "flabellum" or ceremonial fan was presented to the church by Theoldalinda, 6th century Queen of the Lombards. A 9th century "flabellum" from the abbey church of Tournus on the Saône, France is in the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence. Both fans have folding vellum strips that unfold to form cockades, attached to cylindrical handles of elaborately carved bone, which also form boxes or guards for the leaves when closed.

From the 6th to 15th centuries, Christian ritual fans were used in the eastern Mediterranean. According to Apostolic constitutions two deacons, each holding a rigid flag-type fan on a long stick, officiated on each side of the altar before and after the prayers of consecration to keep away marauding flies. The insects were considered representative of evil and the fan breeze associated with the Holy Spirit, which sacred symbolism excluded "flabella" use outside church ritual.

Fans were listed in inventories (1214AD, 1298AD and 1495AD) of churches in England. One church warden lists "a bessume of pekoks fethers". It has been suggested that the introduction of the bell to ward off insects (evil) may have been responsible for discontinued role of the fan in Christian churches.

In Europe, the popularity of the fan as a fashion accessory was undoubtedly spread by Catherine de Medici (1519-89), whose dowry included fans when she married Henry II of France. 16th century European fans were mainly handscreens, feathers of diverse colors and species, frequently ostrich, set in leather at the base of the plume and attached to handles, usually of precious metal encrusted with jewels. Queen Elizabeth I possessed such fans.

The folding fan, made in Italy initially, then in France, England and Holland, quickly became more popular than the rigid hand screen due to its novelty and convenience. The painted leaves usually depicted mythological scenes and the fan sticks were simple and unadorned, unlike the handles of the hand screens.

Records from the end of the 17th century show an enormous quantity of goods, such as tea, textiles, porcelain, lacquer work, fans and fan sticks, imported from the East. According to the East India Company Letter Book, 2,000 fans made of the finest and richest lacquer sticks could be bought in Canton and Amoy in 1699. However, the fans exported from China to Europe were made for European taste and were unlike fans used in China.

Reaching its peak in popularity by the late 17th and 18th century, the fan gained importance as an indispensable accouterment of fashionable dress, and for its unsurpassed artistic and crafted excellence. The well-dressed women possessed a fan for every occasion, and was obliged to handle it properly.

The folding leaves of the fans in this period were of thin kid-like leather (painstakingly manufactured from skin of animals, such as calves, sheep, goats and pigs) and of silk, lace or paper, and were hand-painted or engraved and hand-colored. The sticks and guards were of ivory, bone, mother-of-pearl, tortoiseshell, lacquered wood, skillfully shaped, carved, painted, pierced, inlaid, gilded and silvered in various combinations.

The design and size of fans changed with fashion, reflecting current tastes in art, literature, architecture and costume. During the early part of this period, a story-telling mythological or biblical scene was usually depicted on the leaf. Attempting to compete with the influx of authentic imports, fans imitated Chinese ones, with fanciful figures, pagodas, gardens, and other oriental motifs, which catered to the craze for exotic Chinoiserie design.

In the mid-18th century fan leaves were designed with medallions showing idealized pastoral, romantic, commemorative and domestic scenes. At the end of the century, designs of classical nature were popular, especially scenes of Italian ruins with Greek decorative motifs, valued as souvenirs of the "Grand Tour". Inexpensive printed fans for the middle class frequently served as conversation pieces, offering political topics, games, riddles, calendars, maps, dance steps and so on.

The "brisé fan", a folding fan on which the sticks widen from the base, at the rivet, to the top of the fan where they are connected by ribbon, became fashionable briefly at the beginning and again at the end of the 18th century. The brisé fan has no leaf, all the painting appearing directly on the sticks, which are ivory, bone, horn and lacquered wood, sometimes decoratively pierced.

During the early part of the 19th century the use of fans waned. Fans of this era, in deference to the current fashion silhouette of sheer white muslin gowns, were small, in the Grecian style, and trimmed with spangle and embroidery designs rather than painted.

This style changed, however, when the Duchess de Berry gave an elaborate ball in 1829, to which guests were required to wear Louis XV costumes, a challenge that sent them scouring Paris for elaborate antique fans. Their scarcity instigated a new industry specializing in 18th century fan reproductions.

With the advent of the large hoop skirts, the size of fans in the 1860's grew proportionately. Romantic and retrospective subjects appeared on lithographed leaves, accented with very ornate sticks.

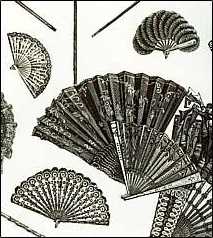

|

| Victorian fans |

During the "Belle Époque", fashion came to reflect the present rather than the past, depicting contemporary scenes and influences of Japanese art. Even impressionist painters like Degas, Gaugin, Pissaro, Monet, painted fans, intrigued with the challenge of the leaf shape.

Motifs of sinuous naturalistic designs were considered chic and new. Fans were beautifully made of tinted mother-of-pearl, synthetic horn and tortoiseshell, and exotic woods. Flamboyant feather fans were fashionable, as were sequined and hand-painted fans.

For the first time Western fans were being signed by the artists. Duvelleroy and Alexandre were fan merchants in Paris and London who made elegant fans to be worn with ball gowns.

After the First World War, women's values and life styles changed radically and beautiful fans no longer became a necessity for the well-dressed woman. By then fans were only carried to keep cool before the advent of air-conditioning.

Then the age of consumerism and advertising arrived. Restaurants, hotels, department stores, cognac and champagne makers, funeral homes, patent medicine manufacturers, perfume companies eagerly seized upon the inexpensive paper fan to print free advertising for customers. These bright fan leaves were skillfully designed by artists to be appealing, and offer interesting commentary on post-war life.

Collecting fans is a fascinating pursuit. A favorite hobby early this century, but fading in popularity for decades later, fan collecting in the past twenty years has again been revived. Museums worldwide now mount exhibitions of fans, and excellent books on fans are being published after a hiatus of almost sixty years. Demand and prices for fans at auction drastically increase every year.

To view fine collections of fans, try visiting the Fan Museum in Greenwich, London and DeFaecher Kabinett in Bieldefeld, Germany, which are devoted exclusively to fans. The Metropolitan Museum , Cooper-Hewitt Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Ringling Museum, Victoria and Albert Museum and Brighton Museum have special collections, seen by appointment only.

Colin Lawton Johnson is editor of the newsletter for the Fan Association of America

Recommended reading on the subject includes:

FANS, by Avril Hart & Emma Taylor, which looks at fans from the 17th century to the present, illustrated with examples from the Victoria & Albert Museum’s dress collection. 67 color plates, 25 b/w illus., 128 pp., hardcover.

To purchase this or other books about fans, you can order online