Dressing

in Top Hat

By

Nancy Lyons

On 15 January 1797, John Hetherington, a hat-maker on the Strand in London, stepped out wearing the first top hat. He created such a sensation that four women fainted, pedestrians booed and a little boy broke his arm. Hetherington was arrested for wearing "a tall structure having a shiny lustre calculated to alarm timid people". He even had to pay 500 pounds for breaching the peace.

|

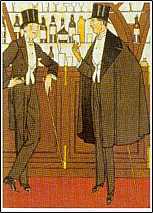

| La Cape Noire (The Black Cape), from Gazette du Bon Ton, c1913 |

However, perhaps because of their flashiness, soon afterwards top hats with tall crowns and curled brims had become the must-have fashion accessory. Throughout the 19th century they continued to be the preferred headgear of elegant bourgeois gentlemen. Top hats were stiff and silk covered, and were worn with suits or dress coats. The morning suit and "topper" were typical dress for gentlemen spending the day at the races.

However, top hats appeared most elegant in the evening when their silky sheen reflected the light. They were made of delicate fabric requiring a great deal of care. For the best luster, they were brushed with a velvet pad and occasionally ironed by a hatter.

Perhaps for these very reasons, top hats lost their popularity by the Turn of the Century. Men were still expected to wear hats in public, although the top hat was thought of as heavy, awkward, expensive and demanding high maintenance.

As a result of its declining popularity, the rituals and habits that defined top hat etiquette were slowly being ignored. Already by the late 19th century, a top hat could be left on at a café, at the pastry shop, in stores, and during intermission of a play, but had to be taken off when accompanying a woman to her dressmaker or milliner. A top hat would be tipped when entering a public place, but only if women were present. When visiting, a man was supposed to always keep his top hat in hand, never setting it down (similar to his cane) or to set it only so the outside could be seen. Greeting one with the hat upturned reminded others of holding out a hat for charity. Already in 1908, a French booklet described the "Rise and Fall of the Top Hat".

After World War I, top hats were only worn for a ceremonial events such as weddings, at the racetrack or for formal evening dress. For evening wear, a "Gibus" top hat or "Chapeau Bras" carried flat under the arm, remained in vogue.

The return of the collapsible opera hat probably hastened the decline of the top hat. The opera hat was collapsible, as the crown was supported by a spiral steel spring enclosed in the lining. This allowed the wearer to fold it so that it could be carried flat under the arm, and would easily go under his seat at the opera house or theater. Quality top hats were made of beaver, felt or silk. Some were made of rubber to achieve the same effect. They were lightweight (less than 6 oz), waterproofed and had a deep shine. Old top hats were sometimes given a second life, after being stripped down, cleaned, reblocked, refinished and polished.